Missing from the Atlanta Opera repertoire for almost a decade, Verdi’s Rigoletto returned the Cobb Energy Performing Arts Center this past Saturday, opening the Atlanta Opera’s 2023-24 season of mainstage productions. As in the case with the previous presentation of Verdi’s middle period masterpiece which took place in March of 2015, this production of Rigoletto (a co-production between the Atlanta Opera, Houston Grand Opera and the Dallas Opera) is conceptual, though this time around it goes further than its predecessor in its attempt to recreate some of the effects that the composer may have originally had in mind.

Through the work of his scenic designer, Erhard Rom, stage director Tomer Zvulun underlines the opera’s oppressive qualities by lifting the action from Renaissance Verona to 1930’s Fascist Italy.

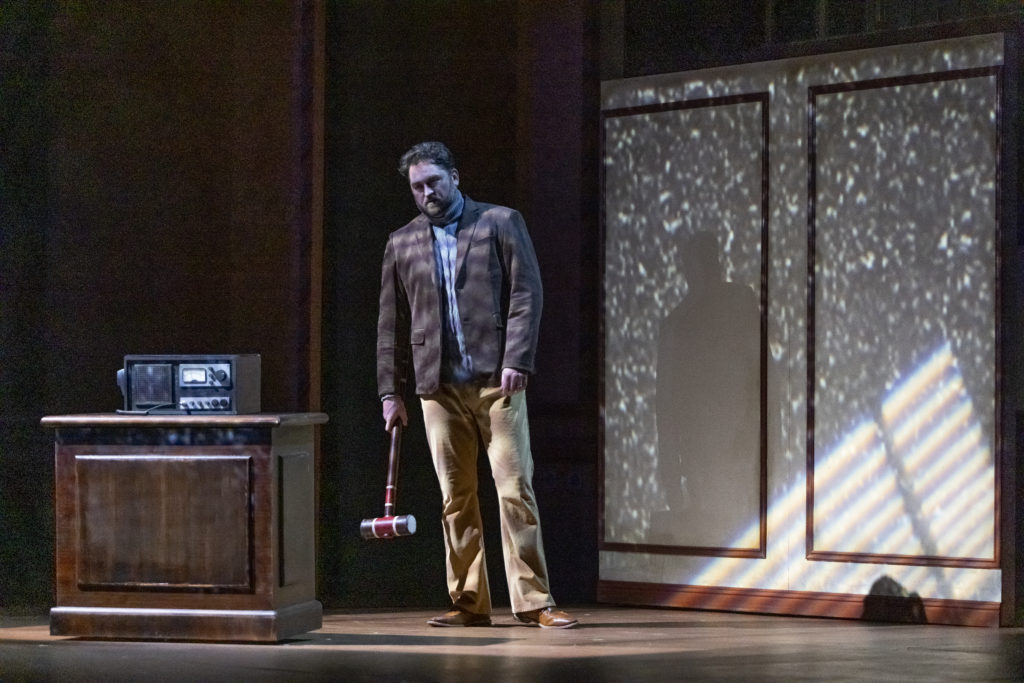

Though the period update adds little to the value of the production (fellow traditionalists must remember that even Verdi’s setting is at odds with the score’s Gallic tinta), Mr. Zvulun’s revamping sought to re-establish elements of vulgarity and violence, particularly those involving the chorus of courtiers, which Verdi elevated to the status of a fully fleshed character in this opera. We know that Verdi was forced to water down scenes of excessive depravity by the censors, yet he was drawn to the more controversial elements of the source material, Victor Hugo’s Le Roi s’amuse” – A hedonistic king, egged on by a savage and decadent court, his every misdeed underwritten by his court jester, sets the stage for a profound study of socio-political inequality and moral corruption through the most unique anti-hero in all of opera: The deformed Rigoletto. Taking these facts into consideration, many of Mr. Zvulun’s riskier decisions are often defensible: The murder of Monterone and his daughter in the first scene sets the tone for this very dark and vulgar society where gang rule and criminal intent wins the day, and will soon overtake the fragile barriers protecting Rigoletto’s idyllic private inner sanctum. It is a world where innocence has no chance, and will be, perhaps somewhat willingly, corrupted. Another expressive scene (wonderfully choreographed by Ricardo Aponte) depicts the reaction of the courtiers as they block Rigoletto’s attempt to rescue Gilda in the second act. As the jester rants and raves, they are almost convinced by his plight and remove their masks, as if they too know the difference in their position is razor thin (#parisiamo) only to reject his pleas and, one by one, revert to their original position (Marullo being the last naysayer). When Rigoletto arrives to collect his victim in the final act, he wears the full clown regalia which defines his position in the Duke’s court, and society at large, symbolizing justice for the servant – the lesser man – over the oppression of the mighty, a visual which further invigorates the irony of the opera’s final twist. Putting a bow on an overall valid and successful reinterpretation of the opera (and how often do I get to say this?), director Zvulun revisits the 2015 Atlanta Opera production of Rigoletto in his interpretation of Gilda’s death, and his efforts are more congruent with the concept this time around.

Leading the charge from the podium, maestro Roberto Kalb made his Atlanta Opera debut with these performances of the critical edition of Rigoletto’s score, and the opening night impression was uneven. His baton inspired crisp and tidy execution from the pit, resulting in a wall of sound both well-defined and sufficiently transparent to allow the voices (both the large and the less sumptuous) their due spotlight without palpable struggle. His brisk tempi, however, often found him at odds with the pacing capabilities of his leads, and he threatened to zip past them or hindered their ensemble efforts in many instances.

It has often been said that in order to properly present operas of Verdi’s middle period, one must simply assemble the best singers in the world. For this production of Rigoletto, the scale tips in favor to what essentially amounts to an ensemble effort (particularly when compared to the 2015 line-up, which boasted Todd Thomas, Nadine Serra and Scott Quinn for those who keep track of such things). Opera should also function as a vehicle for great singers (we can truly count one exception,) so this is hardly a compliment. The debut of tenor Won Whi Choi as the Duke raised the eyebrow, as the young singer performance revealed a mixture of disparate vocal endowment and miraculous execution. As heard on opening night, Mr. Choi’s method betrayed signs of many strings employed to puff up an output, his entrance in the first scene revealing an instrument devoid of a definite core, and an overall breathy production which navigated the scale in an alarmingly disconnected fashion. Towards the end of the secene, his interactions with the chorus (Gran nuova!) found him scrambling – a bad omen looming over his debut so early in the evening. Thankfully, he was able to assert himself as the performance wore on. His duet with the prima donna in the second scene found him leaning heavily on the use of head voice, and what some may disapprovingly refer to as “crooning” – and yet he managed to cleverly convey the suave and tender lover nonetheless despite these shortcomings. The opera’s second act found Mr. Choi now fully acclimated to the maestro’s leadership and the dimensions of the hall. His great scena, beginning with the extended dramatic recitative “Ella mi fu rapita!” leading to the cavatina “Parmi veder le lagrime” was confidently executed, though, as in the case with the reinserted cabaletta “Possente amor mi chiama” and the opera’s big tune in the third act (y’all know it), his singing was riddled with a similar lack of uniformity in tone production and general method, often striking the ear as a series of giant sighs stitched together. While Mr. Choi was well applauded at the end of the performance, the fundamental features which should promote great singing and an important career (equalized registers, clarity in emission, elegant and expressive phrasing, a mastery of dynamics, beauty of tone, trumpet-like squillo, ad nauseum…) are yet within his reach.

Previously heard at the Atlanta Opera as Cleopatra in Handel’s Giulio Cesare in 2021, Jasmine Habersham fared better as Rigoletto’s daughter, Gilda, and distinguished her interpretation with earnest singing, a practice which may fall prey to its own assortment of pitfalls, yet is often bound to produce greater rewards. Armed with a high soprano with a definite edge, Ms. Habersham’s voice is full-bodied, well-produced, and dynamic enough to be convince in the heroine’s three very different scenes. For the first, and perhaps most challenging to her essentially lyric instrument, her approach was disciplined, favoring a clean execution of the score, particularly the intricate picchiettati of her showstopping aria “Caro nome”. Her handling of these pages, often associated with the coloratura soprano brand, was accomplished, though there is evident tightness and flatness above high C, implying that these notes in the scale are on temporary loan for the time being, and the trill deserves a better exponent. She was most successful in the extended duets with her father in the opera’s second and third acts, which allowed her to fill the phrases in ways better suited to her talents. Her stage business is involved and often touching, and while her voice is pleasing and projects a perky charm, it lacks a certain glamour that would make her ascend to the big leagues an easier ordeal. We suspect that she’s likely to welcome such challenges for she’s already surpassed the original impression made in her debut only two years ago.

In the title role, Georgian baritone George Gagnidze makes his Atlanta Opera debut in the part that has earned him critical acclaim around the world. His performance as Rigoletto, as heard last Saturday, is moving, well-balanced, and artfully achieved. He was the highlight of the evening, at every turn, taking advantage of the role’s unique opportunities to express the passions of a man condemned by his actions and nature through a malleable baritone responsive to the singer’s interpretation. His declamation is also descriptive, making for a rich and profound reading of Rigoletto’s famous soliloquy “Pari siamo”, an intense and pathetic “Cortiggiani”, and a chilling note during the introspective recitative while awaiting receipt of the body of the Duke. The duets with Gilda are the heart of this opera, and Mr. Gagnidze rose to the occasion through his consummate vocalism. Nostalgic, tender and overprotective in the first, he allowed the phrases to swell nostalgically at the memory of his dead lover (Deh non parlare al misero), only to morph into a stern warning of the dangers of the outside world. By the time we arrived at the scene where Rigoletto’s concerns have been tragically fulfilled, Mr. Gagnidze’s instrument turned pathetic as he consoled the weeping Gilda. Though the duet’s famous stretta, “Si, vendetta…” got a bit out of hand under the pacing of maestro Kalb, Mr. Gagnidze prevailed in expressing his laser-focused intent as he sets his eyes towards vengeance. The final trio was devastating and touched the heart. In terms of vocal prowess, it must be admitted that Mr. Gagnidze’s instrument has lost some of the size and glamorous verve that got the world’s attention some fifteen years ago. In its place, his interpretation of Verdi’s iconic jester has deepened, and more than makes up for some dry patches in his scale.

The secondary parts were solidly cast, and as noted below, delivered surprises. In the small, yet important role of Count Monterone, bass baritone David Crawford was effective in his delivery of the crucial curse which hovers over the proceedings. As Maddalena, mezzo-soprano Olivia Vote’s overtly vulgar disposition often distracted from her considerable vocal endowment. For those able to focus past the bump and grind, hers remains a serviceable instrument consistent with our recollection of her performance as Mary in Wagner’s Der Fliegende Hollander six years ago.

The case of her stage brother, the assassin Sparafucile, deserves special mention. The part was entrusted to the gifted Patrick Guetti, who, like several others, made his Atlanta Opera debut in this production. The young bass has been favored by the gods, who bestowed upon him a voice for opera and a face for Instagram. His bass is naturally sumptuous, remains rich at the bottom of the scale, and as in the case of the company’s previous Sparafucile (the fabulous Morris Robinson) will dominate the ensemble with seemingly little effort. This was made evident in the scene where Sparafucile encounters Rigoletto for the first time. The scene is unique in Verdi’s cannon in that the orchestra is reduced to a chamber dynamic and calls the participation of low pitched instruments, thus placing the principal vocal line on top. Markings like morendo and pianissimo, imply a nefarious, secretive exchange in a darkened alley. Perhaps dealing with opening night jitters, Mr. Guetti overcooked his efforts, ensuring that the whole of Mantua and surrounding Cobb County were notified of his services and availability. He repeated this foul during the opera’s final scene, and while its odd to question the availability of big vo icesin opera, this is still Verdi’s world, where even bodybuilders are expected to dance on tip toes. Based on the strength of last Saturday’s performance, Mr. Guetti has yet to become an important artist, though the promise is there – and please believe – I will be in the audience egging him on once he gets there.

The remainder of the cast was entrusted to the artists of the Glynn Studio, with the clarion voice of mezzo-soprano Aubrey Odle as Giovanna representing the best efforts of the company’s young artist program.

The Atlanta Opera run of Verdi’s Rigoletto will end this Sunday, November 12th. To get tickets for this performance, or to get more information about the rest of the Atlanta Opera’s exciting 2023-24 season, please visit the company’s website at www.atlantaopera.org

-Daniel Vasquez